Respond to Limited or No Labeled Data in The Realm of NLP

Published:

Lack of labeled data for training is such a cliché in the data science and AI field. In data science, only large companies which accumulated sufficient user or machine records bother to research fancy predictive models to obtain a systematic understanding of the patterns with statistical evidence. Regarding AI, the algorithm development was once stuck at a bottleneck until the huge ImageNet dataset was open sourced which led to a blossom of neural network research in computer vision. In NLP, a decent, large go-to training set is still missing. To overcome this issue, researchers made enormous amount of effort in pre-training zero-shot or few-shot large language models from plain text.

These language models have evolved to comprehend syntax and semantics well enough to generate new text. However, to achieve a tailored task in a specific domain, such as to categorize topics, which involves external labeling, fine-tuning the language models to adapt to the task is necessary. This step still requires labeled data. Plus, considering the usual gigantic set of parameters each language model uses, a decent amount of data is usually the blocker of model development.

In this blog post, I would like to introduce a few approaches that we took in our NLP capstone project with Adobe. Leveraging a few thousand training data points and machine learning techniques, we managed to design cool functions for business contract analysis and scale up to any given contract.

Project Background

To begin with, our client, Document Intelligence Labs (DIL) at Adobe Research, provided us a collection of raw business contracts, few thousand sentences with labeled condition and action phrases, and a completely open-ended problem statement that has something to do with condition clauses.

Before anything can be done, we need more data. We urgently need some tool to map the existing set of labels onto a large dataset, ideally within a specific domain. This is our first task against lack of labeled data.

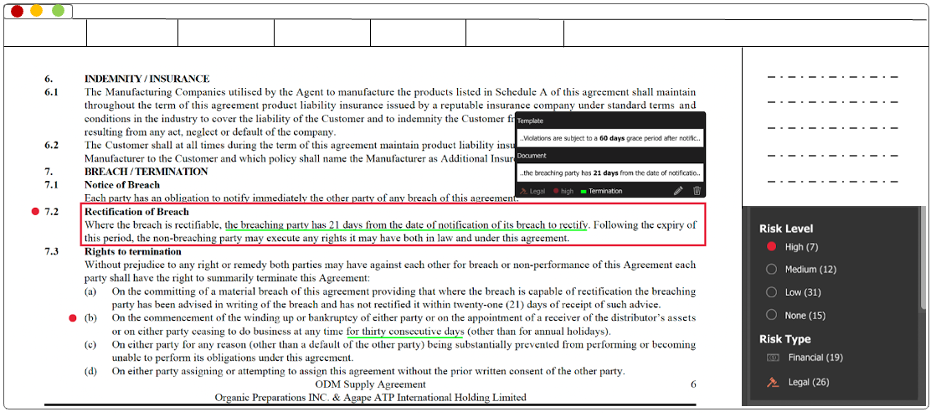

With the collaborative skillsets of the team and a number of debates, we narrowed our topic down to building a risk analyzer for supply contracts embedded in Adobe Acrobat that annotate the risk level and risk type of each condition clause. The prototyped implementation of this idea is shown below. Then here comes our second challenge which is again the labeling of risk level and type.

Caption: The de-identified prototype of the front-end development. Client company info was deidentified.

So far, none of our ideas were heading towards a bright, certain direction. At that moment, we went back and forth on what was feasible in our objectives and made trials and errors with the technical approaches. Eventually, we found the following methods successful in addressing or bypassing the problem of lack of data in this project. I will be unwinding each of them in the rest of the post. Hopefully, these would offer an idea or two to those who are suffering from the same issue.

- Converting unstructured data to structured and framing the problem as a classic machine learning predictive task

- Using semi-supervised learning in place of supervised learning

- Incorporating large language models pre-trained on massive data

- Involving human in the loop

Detailed Approaches

1. Unstructured to structured, deep net to classic machine learning

Having a model that extracts condition clauses from raw contracts is a huge scope for the number of labeled clauses we have. The first thing I did was to shrink the search space by defining the model to be a binary classifier. This way, the scope is down to predicting yes or no with possibly a classic machine learning algorithm which involves much fewer parameters, hence much smaller dataset required.

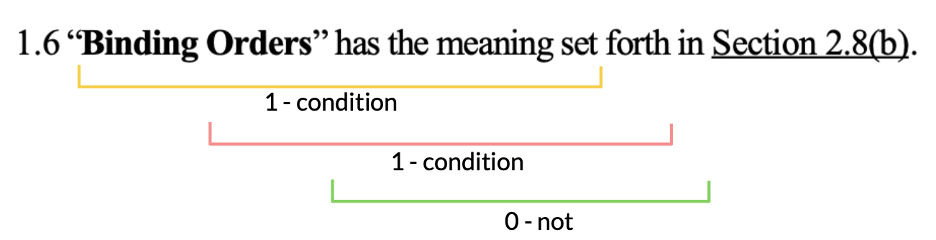

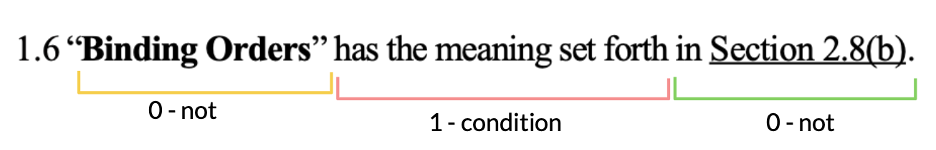

Then in terms of constructing data points, I come up with two approaches. One is to treat each contract as a block of text and run a sliding window down through it. At each position, words within the window are collected as one data point. Depending on whether this window falls within a condition clause, the data point is labeled as 1 or 0. The graph below illustrates this idea. With this approach, we generated ~330k data points. For inference, contracts are broken down in the same way and consecutive positive predictions with high confidence are predicted as condition clauses. This structured dataset allowed me to apply algorithms like KNN and gradient boosting. With a few other tricks, this yielded a nice accuracy (81%).

Caption: illustration of data construction with a sliding text window

A variation of this approach to construct dataset is to take out the labeled condition clauses from each sentence as a positive data point and take the rest pieces of the sentences as negative points. This is illustrated below. This approach generates much fewer data points (~ 5k) but greatly suits the classic sentiment analysis algorithm, Naïve Bayes. With this approach, I obtained a model with a great precision score which even better suits our use case.

Caption: illustration of data construction with partitioned sentences

2. Supervised to semi-supervised learning

Since we lack the risk level labeling for either sentences or documents, we are limited outside of supervised learning. Our solution to this struggle came from a collection of ideas of my wise teammates. We decided to label a few classic documents high, medium, or low risk as reference. The better version of this in real products is to have users upload their previous contracts as templates. By calculating the semantic similarity between these and a new contract, we can estimate its risk level.

3. Incorporating large pre-trained language models

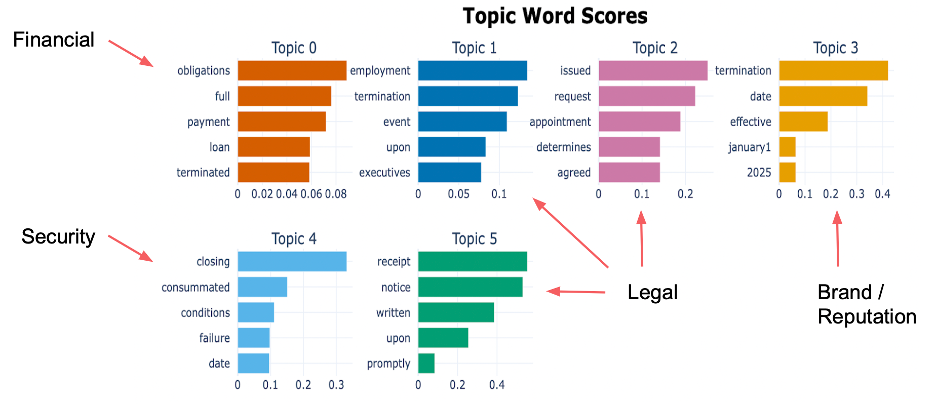

In the task of categorizing risk types, my teammate took advantage of the BERTopic, a transformer-based language model pretrained on massive data, and categorized the likely topic each word in a condition clause belongs to. Looking at all words in a clause, he was able to pick out the most likely topic this clause falls into. The topics we considered include financial, legal, security, and reputation risk. The chart below gives some examples of the most representative words in each topic.

Caption: top words identified for each relevant topic

Since the pre-trained model has demonstrated to have a good understanding of the semantics of English sentences, we bypassed the challenge of training such a model from scratch. Essentially, by using the pre-trained model, we gratefully stand on the shoulder of the giants.

4. Human in the loop

Last but not the least, our coach client brought in a great practice in all product development, which is to continuously improve the algorithm by welcoming users to pick out mis-predictions given specific contexts they consider. Don’t be struggled to make a perfect model all at once. Often time it’s impossible too. Instead, having the initial users contribute to the development while benefiting them with the existing functions.